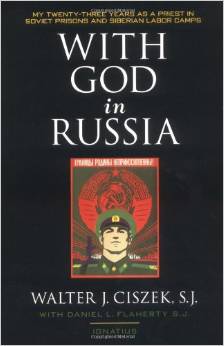

I was recommended this book by a parishioner and then found it on sale at the local Catholic goods shop. It was originally published in 1964 and then again by Ignatius Press in 1997. It relates the story of a Jesuit trained to operate “behind enemy lines,” behind what later became known as the “Iron Curtain,” Post-Soviet Russia. A Polish Catholic from Pennsylvania, who always seemed to push his physical stamina as a boy, indeed an unlikely Jesuit, he pressed forward towards the prize of the Society of Jesus almost as if it was simply the fact that they were the best, the elite, the most hard-core, that attracted him.

He felt called to this special mission to Russia and spent years learning how to operate under the “Oriental Rite” or, as we call it today, Byzantine Rite. He couldn’t stand learning it and he doesn’t give any indication that his love for the tradition grew much over the years. Although there are Pols who use the Byzantine Rite, there is generally no love-loss between Pols and Russians and his prejudice as a Polish American showed through in this, and yet he persevered. He spent a little time in Rome after becoming a Jesuit, training at their center for Byzantine or Oriental studies. Then he ended up in Poland, serving parishes during WWII. Then he ended up in prison, rather quickly, as a “spy” for the Vatican.

I found the book incredibly comforting as a Bi-vocational Priest. (I read it while serving as a Security Guard. I read it, often, while feeling sorry for myself.) But his way of just taking the “sacramental moment” as it comes, his taking seriously the prayer of St. Ignatius of Loyola, “Wherever thy glory best be served, whenever, however” was inspirational. For example, he might spend a year at a prison in which he had library rights, and then he would say matter-of-factly that he spent the year reading. He didn’t say mass for years or months at a time, and then he would suddenly find himself in a camp where he was overwhelmed by pastoral duties. After being released from prison, although everybody knew he was an American, he was practically a Russian citizen and served pastorally in two different cities. His success pastorally was almost sudden, revival-like. And in both cities sudden was his invitation to leave those cities. Post-prison, after he’d been warned in a third city not to do any pastoral duties, he states again matter-of-factly that he had saved his money in the previous city and, given the fact that he’d worked hard labor for fifteen years in prison, he figured he’d let himself take a year off. When the authorities started to wonder why he wasn’t working, he simply went back to work again.

The value of this book is not only that one can learn coping mechanisms for times of persecution and prison, one can learn coping mechanisms for how to deal with times when one gets to “be a priest” and when one doesn’t. He admits his times of depression, but his discipline as a Jesuit never ends and this carries him through. He continues to make his daily Ignatian meditations, say his prayers and, when possible, his daily mass and he even finds ways to give lectures to fellow priests or hone his sermon skills. He understands, or perhaps learns to understand, that “down time” is never “down time” but polishing, resting, honing – always waiting for the next pastoral interaction, even if years in the future.

There are times, albeit short, that he doesn’t work because, as he puts it, the people take care of his needs. But those times are very brief. Most of the time he is doing what he trained to do, but it takes longer to get to those mountain views when he could see that he is doing what he was called to do than he would like. Many of us feel that way. Many of us struggle with the same things. I couldn’t help but feel that in this post-Christian country of America we are already operating frighteningly similarly to those priests in Soviet Russia. In fact, I think it is a good read for any minister today, in order to prepare for the persecution that is coming.

Like reading a novel, towards the end of the book, I couldn’t put it down. I wanted to see how he got out of Russia. The parishioner who recommended this book knew some folks who would travel to see this priest somewhere in Pennsylvania after his return from Russia. These folks referred to this priest as simply “The Confessor”. So one might assume that after those years in Russia, hearing the confessions of convicted criminals and those constricted by Communism, he returned to America a very good Father Confessor indeed.

The morning after I finished the book, I went to church and found that the parishioner who recommended this to me had already bought me the sequel, “He Leadeth Me.” And I look forward to that as well.

He felt called to this special mission to Russia and spent years learning how to operate under the “Oriental Rite” or, as we call it today, Byzantine Rite. He couldn’t stand learning it and he doesn’t give any indication that his love for the tradition grew much over the years. Although there are Pols who use the Byzantine Rite, there is generally no love-loss between Pols and Russians and his prejudice as a Polish American showed through in this, and yet he persevered. He spent a little time in Rome after becoming a Jesuit, training at their center for Byzantine or Oriental studies. Then he ended up in Poland, serving parishes during WWII. Then he ended up in prison, rather quickly, as a “spy” for the Vatican.

I found the book incredibly comforting as a Bi-vocational Priest. (I read it while serving as a Security Guard. I read it, often, while feeling sorry for myself.) But his way of just taking the “sacramental moment” as it comes, his taking seriously the prayer of St. Ignatius of Loyola, “Wherever thy glory best be served, whenever, however” was inspirational. For example, he might spend a year at a prison in which he had library rights, and then he would say matter-of-factly that he spent the year reading. He didn’t say mass for years or months at a time, and then he would suddenly find himself in a camp where he was overwhelmed by pastoral duties. After being released from prison, although everybody knew he was an American, he was practically a Russian citizen and served pastorally in two different cities. His success pastorally was almost sudden, revival-like. And in both cities sudden was his invitation to leave those cities. Post-prison, after he’d been warned in a third city not to do any pastoral duties, he states again matter-of-factly that he had saved his money in the previous city and, given the fact that he’d worked hard labor for fifteen years in prison, he figured he’d let himself take a year off. When the authorities started to wonder why he wasn’t working, he simply went back to work again.

The value of this book is not only that one can learn coping mechanisms for times of persecution and prison, one can learn coping mechanisms for how to deal with times when one gets to “be a priest” and when one doesn’t. He admits his times of depression, but his discipline as a Jesuit never ends and this carries him through. He continues to make his daily Ignatian meditations, say his prayers and, when possible, his daily mass and he even finds ways to give lectures to fellow priests or hone his sermon skills. He understands, or perhaps learns to understand, that “down time” is never “down time” but polishing, resting, honing – always waiting for the next pastoral interaction, even if years in the future.

There are times, albeit short, that he doesn’t work because, as he puts it, the people take care of his needs. But those times are very brief. Most of the time he is doing what he trained to do, but it takes longer to get to those mountain views when he could see that he is doing what he was called to do than he would like. Many of us feel that way. Many of us struggle with the same things. I couldn’t help but feel that in this post-Christian country of America we are already operating frighteningly similarly to those priests in Soviet Russia. In fact, I think it is a good read for any minister today, in order to prepare for the persecution that is coming.

Like reading a novel, towards the end of the book, I couldn’t put it down. I wanted to see how he got out of Russia. The parishioner who recommended this book knew some folks who would travel to see this priest somewhere in Pennsylvania after his return from Russia. These folks referred to this priest as simply “The Confessor”. So one might assume that after those years in Russia, hearing the confessions of convicted criminals and those constricted by Communism, he returned to America a very good Father Confessor indeed.

The morning after I finished the book, I went to church and found that the parishioner who recommended this to me had already bought me the sequel, “He Leadeth Me.” And I look forward to that as well.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed